Roland and Durendal

In December 2025 I returned once again to Rome, where I revisited many of the ancient sites I so enjoy, and, as ever, searched for fresh places and things I had yet to see in over 30 years of journeying to the Eternal City, including the Horrea Piperataria, Horti Sallustiani, Museo Ninfeo, Centrale Montemartini, Sessorian Palace and Museo delle Mura.

Only 5 minutes from the apartment where I stay, the Vicolo della Spada d'Orlando (Alley of the Sword of Roland), where, as the name suggests, lies a curious embedded, deeply gashed stone long associated with Charlemagne's heroic knight Roland.

The stone itself (and some scant remains opposite) is a diminished base of a cipollino marble column, part of a temple built in AD 119 and dedicated to the Emperor Hadrian’s mother-in-law Matidia.

Two legends are associated with the rock, both featuring Roland and his legendary sword Durendal. Durendal was the sharpest sword on Earth, capable of cutting through giant boulders with a single stroke and unbreakable, as it was chock-full of relics: a tooth from Jesus’ wingman Saint Peter, blood from Saint Basil, a snippet of the Virgin Mary’s robe and a single hair from Saint Denis.

Some say the weapon was forged by Anglo-Saxon deity Wayland; others claim the Emperor Charlemagne had received it directly from an angel and then gave it to stalwart Roland.

As part of the rear guard of Charlemagne’s army, Roland was caught in a Basworsque (not Saracen/Moorish) ambush at Roncesvalles in passes of the Pyrenees in northern Spain. Roland slaughtered thousands with his combat skills and (more importantly) magic sword. But outnumbered and overrun, Roland decided to destroy Durendal to keep it from the Basque hordes. He struck an insanely powerful blow against a solid marble column that for some reason was nearby. But, you guessed it, the blade did not shatter, it cut deeply into the column.

Roland would die at Roncesvalles from blowing his battle horn Oliphant, calling to Charlemagne’s forces that they avenge him. Supposedly, he blew so hard, his head literally exploded and his brains spewed out.

With deadly travail, in stress and pain, Count Roland sounded the mighty strain,

Forth from his mouth the bright blood sprang, And his temples burst for the very pang

But somehow, some way, the piece of marble column with the cut in it made its way to a Roman back street.

Tradition also has it that Roland's Breach in the Pyrenees was created when he attempted to break Durendal and cut a massive gash in the mountainside with one terrific blow; a similar such tale is used to explain gap in the peak of Puig Campana in the Province of Alicante, Spain.

La chanson de Roland (1978): Klaus Kinski as Roland

The second version of the tale is far simpler. Before the Spanish campaign, Roland was in Rome and beset by robbers/assassins. Defending himself, he slashed out in all directions, inadvertently splitting part of a nearby column. Alternatively, after Roncesvalles, Charlemagne, to prevent Durendal from falling into enemy hands, took it to Rome where he attempted to break it against the column.

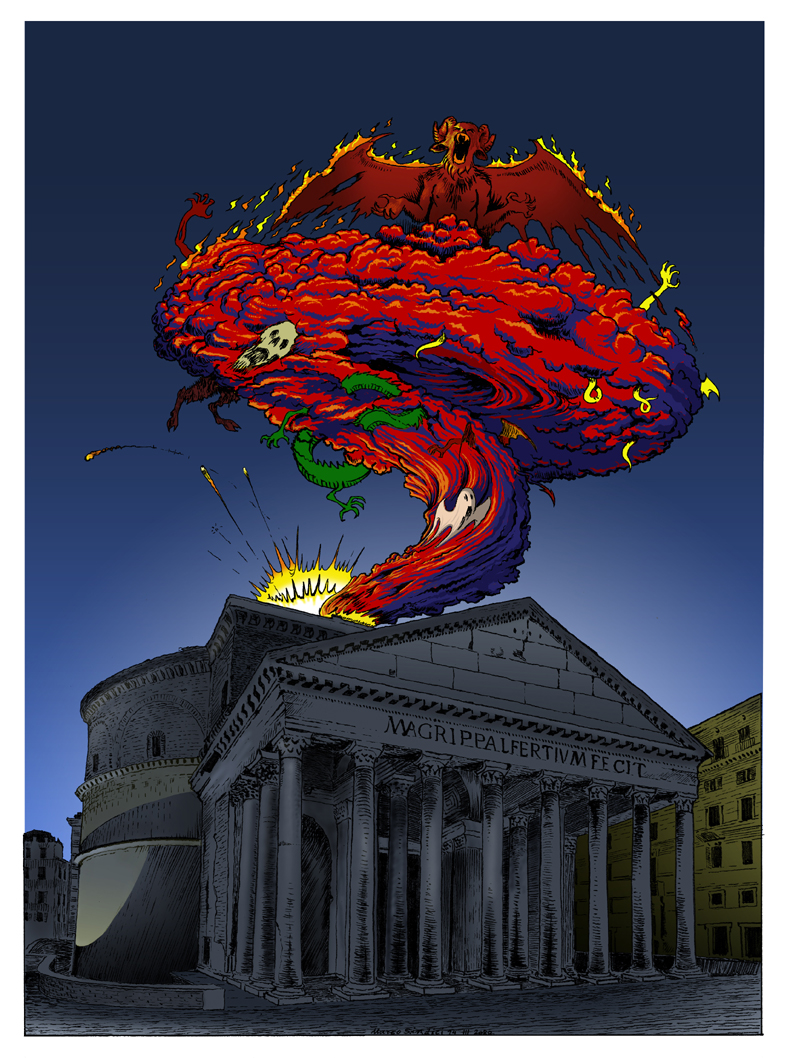

In yet another version, Roland passed through the alley where he was approached by a beautiful courtesan. She attempted to seduce him, but the virtuous Roland saw she was in fact possessed by Satan and, unsheathing his sword, fashioned the hilt into a cross, in an attempt to drive the evil spirit from the woman.

Thus from the poor woman emerged the Devil whom the paladin tried to slay with Durendal, but his attempt was naturally in vain. The Horned One vanished in his customary puff of sulphurous smoke, and Durendal lodged itself temporarily in the rock, causing the crack that can be seen to this very day.

The column:

Piranesi’s drawing of what some of the ruins of the Temple of Matidia looked like in the 18th century

The last of Roland:

Durendal at Rocamadour

The more popular explanation for what happened to Roland’s blade (the “French Excalibur”), the paladin hurled his sword away with superhuman strength (boosted by the Archangel Michael) as the battle went badly at Roncevaux, the sword finally coming to rest hundred of miles away in the French village of Rocamadour (Lot).

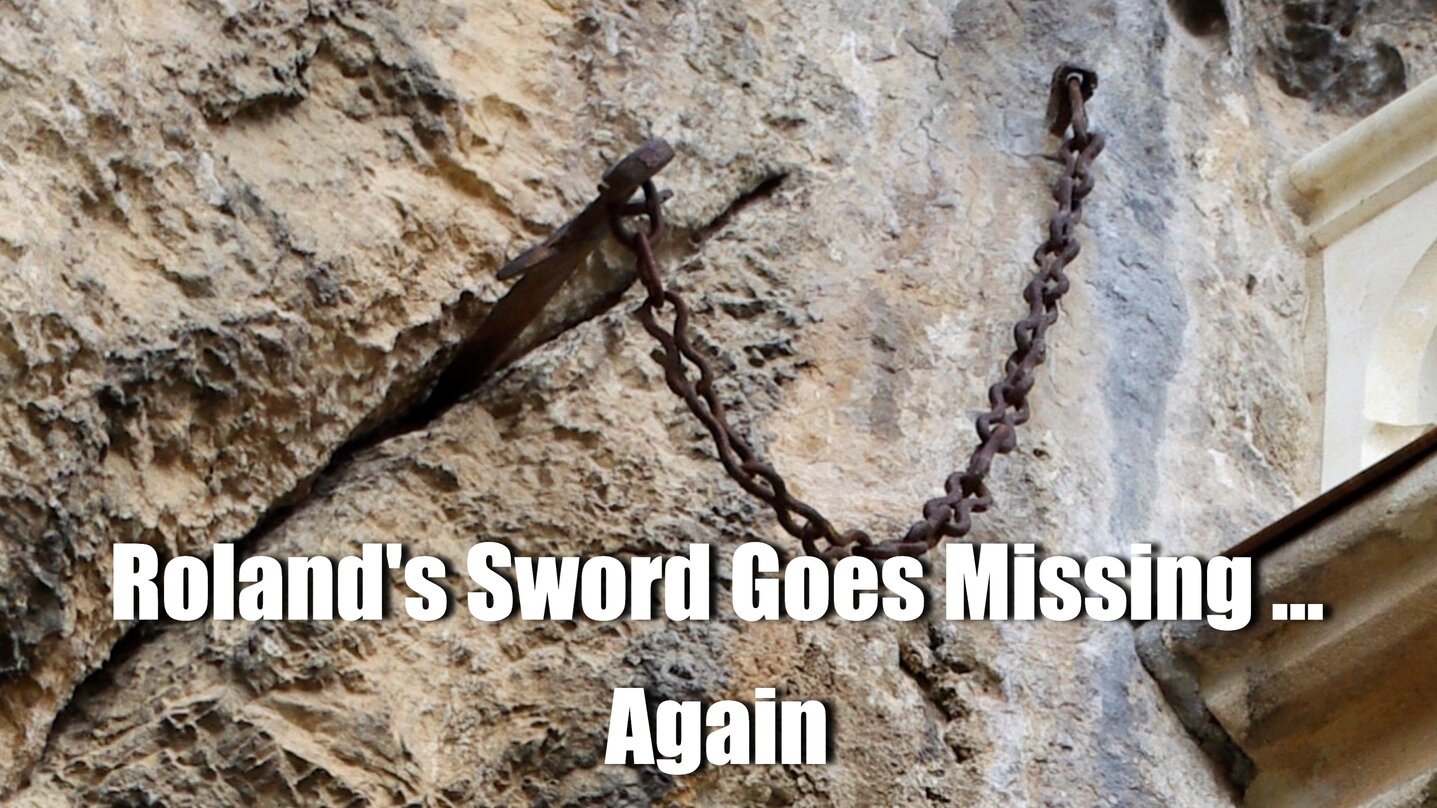

There the mystic weapon was supposedly deposited in the chapel of Mary, but later stolen by Henry the Young King in 1183. All successive replicas have been stolen; most recently the sheet metal sword which was embedded in a cliff wall’s cleft and secured with a chain, pinched in June 2024. There has been some form of Durendal at Rocamadour for 1,300 years, according to the locals.

The London Stone

I’ve visited the London Stone on a fair few times, from when it was a neglected part of a Cannon Street sporting goods store, to its more recent, smartened up home at the same address. The name "London Stone" was first recorded around the year 1100; the date and first purpose of the stone, although could be of Roman origin - a milestone or similar. Claims that it was an object of pre-Roman worship/human sacrifice or has particular occult importance are unsubstantiated.

One frequently told story is that the Stone is in fact the one which Excalibur was famously plunged, to be withdrawn by the young Arthur.

The ‘Real’ Sword in the Stone?

Galgano Guidotti (1148–1181 AD) was a Catholic saint from Tuscany born in Chiusdino, in Siena, Italy.

The son of a local lord, Galgano became a knight, living a licentious life before his famed conversion. Whilst on the road near Siena, his horse threw him into the dust; an ‘invisible’ angel lifted him to his feet and led him to the rugged Monte Siepi. In a vision, the chastened knight saw a round chapel on the hill with Jesus, Mary and their disciples gathered there.

Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It's them twisting it that ruins it for me.” John Lennon

The angel enjoined the lad to repent his many sins, but Galgano protested that he could no more change his wicked ways than split a rock with a sword. To prove his point, he thrust his blade at the rocky ground, but the sword slid like a knife in butter through the living rock, where it remains lodged to this very day.

Galgano settled on the hill as a hermit, like the later St Francis (1181-1226 AD) befriending wild animals, with his lupine pals ripping apart and eating an evil monk sent by Satan himself to kill him. He died in 1181 aged 33 years. Canonization and veneration swiftly followed. In 1184, a circular chapel was built over his tomb; many pilgrims soon visited and miracles were spoken of.

The Sword in the Stone relic can be seen at the Rotonda at Montesiepi, near the ruins of the Abbey of San Galgano. Analysis of the sword’s metal handle conducted in 2001 by Luigi Garlaschelli confirmed that the "composition of the metal and the style are compatible with the era of the legend". Scanning confirmed that the upper part of the sword and the invisible lower one are genuine and belong to the same artifact.

Further reading:

Stephen Arnell’s novel THE GREAT ONE is available on Amazon Kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Great-One-Secret-Memoirs-Pompey-ebook/dp/B0BNLTB2G7

Sample:

No comments:

Post a Comment